Links to all of CRIME STORY’S coverage of the Robert Durst trial are here.

It had all the elements of a classic Susan Berman article or screenplay: Celebrities, the scion of a New York real estate family, tightly held secrets, an anonymous note alerting police to the location of a “cadaver,” and a bi-coastal mystery.

Only this time, the victim was Berman herself, the funny, manipulative, raconteuse with an exotic past who could talk as fast and as long as she could write. Berman, with her trademark dark, shoulder-length hair and bangs drawn across her eyes like window shades, was well known at gathering spots for the cognoscenti, be it Elaine’s in Manhattan or Nate ‘n Al’s deli in Beverly Hills.

It was her body that police found on Christmas Eve 20 years ago today lying in a pool of blood in the back bedroom of a barren bungalow at the edge of Beverly Hills. The paws of her three, wire fox terriers had tracked through her blood by the time the police found her.

There was no shortage of drama or suspects: The gun-toting landlady who had repeatedly sought to evict Berman from the bungalow in Benedict Canyon. The personal manager to whom she owed thousands of dollars. Decrepit gangsters from Las Vegas, the kind of shadowy guys who hung around with her father in the 1940’s and 50’s as they transformed that sleepy desert town into a gambling and entertainment mecca.

“The irony of it is so striking,” said Julie Smith, a journalist, mystery writer and close friend of Berman. “Susan would’ve written about it if it had happened to a friend. Susan drew from her own life. She talked a lot about ‘secrets’ and she conveyed a sense of a person in the know.

“You never knew what she would say or do,” Smith added. “She had a fascinating background. She was an extremely ambitious, very talented, intelligent, but an extremely damaged person.”

LAPD detectives eventually focused their investigation on an entirely different suspect, a man to whom she was so close and so loyal that she considered him a brother, New Yorker Robert A. Durst. If Berman had grown up as a mob princess in Las Vegas, Durst was the princeling of a powerful family whose many skyscrapers helped form the glittering Manhattan skyline.

The deep bond between the two had been forged at U.C.L.A., where they both attended classes in the 1960s. Durst, who insists he did not murder Berman, still describes her as his “best friend.” When she was in financial straits, Susan could count on “Bobby” to throw her a gilded life preserver, including $50,000 not long before her death.

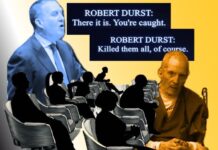

Los Angeles Deputy District Attorney John Lewin contends that as close as he was to Berman, Durst would act in his own mortal interest when he felt cornered. Berman’s murder, he says, was part of a web of misdeeds spanning two decades and three deaths. Durst’s trial for the execution style murder of Berman started in March, 2020, but it was suspended after only two days of testimony because of the pandemic. The trial is scheduled to resume in April.

Susy, her friends say, was intelligent, funny, imperious, a mash-up of confidence and heart-breaking vulnerability. She idolized her father, who was known to his friends, associates and the F.B.I. as Davie “The Jew” Berman, left an indelible stamp on his daughter.

He was the suave, master of ceremonies at the Flamingo and Riviera hotels who knew everyone and just who should get the best room in the hotel, or the best table at a nightclub. His word was law. He fawned over his daughter, hanging her photograph next to the reservations desk at the Flamingo and giving the six-year-old the run of the casino.

Those traits showed up in Susy, who carefully cultivated a network of friends that extended from Hollywood to Manhattan. She could be generous and entertaining, doling out gifts and enthralling her friends with her stories over lunch. At the same time, she would grill waiters mercilessly about a dish, or order a friend take a new pair of boots out to the garbage because she had “decided” they were scuffed. She could also be unforgiving, abruptly cutting off a friend who failed to attend her wedding.

Most of all, Susy absorbed her father’s sense of loyalty, or what some might call “omerta.” And she was most loyal to her friend Durst. “She fought hard not to be the mob girl,” said Smith, “but she had a whole lot of mob values.”

Her career started with so much promise. She wrote screenplays, a half dozen books, and many, many articles. Time and again, she returned to her own life for inspiration. But she insisted on writing her own way and, according to friends, she lived her final years in “dire poverty,” while fending off eviction. She “never lost heart,” clinging to the notion that her big break was still coming. “I see now that Susan’s best stories were always those about Susan,” said Carol Pogash, a reporter who worked with Berman at the San Francisco Examiner in the 1970’s. “Her life was the best drama she ever told.”

My own chase of Berman and Durst began in late 2000 when I was at The New York Times, covering real estate moguls and their grip on the streets and politics of New York. Real estate is a blood sport in New York, but it rarely results in an actual murder. But now, a colleague, Kevin Flynn, and I had gotten a tip that the state police were reopening their investigation into the disappearance of Durst’s first wife, Kathie McCormack Durst. Long-forgotten by all but her family and friends, Kathie Durst was last seen on the night of January 31, 1982, five months before she would have graduated from medical school.

I knew both Durst’s father, Seymour, and his younger brother Douglas, though I had never heard of Robert, who had been estranged from his family since 1994. I never expected his story to follow me through much of my career. Three times, I packed up my files and put them in the attic, only to pull them out when a new chapter opened up.

Early on, Nick Chavin, a close friend of both Durst and Berman, told me I had to talk to “Susy” Berman who knew all of “Bobby’s” secrets. Chavin, at that time, believed that his friend was incapable of violence, let alone killing his wife.

Weeks later, I picked up a New York tabloid with a shocking headline: Berman had been found murdered in her Los Angeles home. Chavin and I flew to LA for her memorial service. Chavin got in. As a member of the press, I was politely turned away. Berman’s friends and family wanted to protect Bobby from being hounded by reporters.

The first thing I learned about Susan was that her father, Davie Berman, was a mobster who ran the Flamingo Hotel with Bugsy Siegel in the 1950s. “He was just my father to me,” Berman wrote in her 1981 memoir, Easy Street; The True Story of a Mob Family, “but to the world he was Davie Berman, one of the founders of the syndicate, a trusted partner of Meyer Lansky, Frank Costello and Bugsy Siegel.”

Over the course of her writing career, Berman interviewed Vice President Gerald Ford, actress and director Liv Ullman, the former Miss America Bess Meyerson, singer Carly Simon, and San Francisco Mayor Joseph Alioto. But she would always return to what she knew best: her life and Las Vegas.

You can find part 2 of this story here.

Charlie Bagli has been covering the Robert Durst mystery for two decades, mostly for The New York Times, but also for Los Angeles Magazine and Town & Country magazine.